Medical Museums | Edinburgh

During the 19th century, the University of Edinburgh’s medical school (first established in 1726) became known as one of the best in the world, and around that time many great pioneering doctors lived and worked in the city, and made many great advancements in the medical field. Their legacy is remembered in the city’s medical related museums, both of which I visited for the first time this year. Surgeons’ Hall was initially a teaching resource, and is now open to the public as a paid entrance museum, housing an exhibition of the history of surgery, and hundreds of pathology specimens, while the Anatomical Museum is still used by current students in the Old Medical School building, and is only open to the public once a month, for free.

Surgeons’ Hall Museums

|

| (source) |

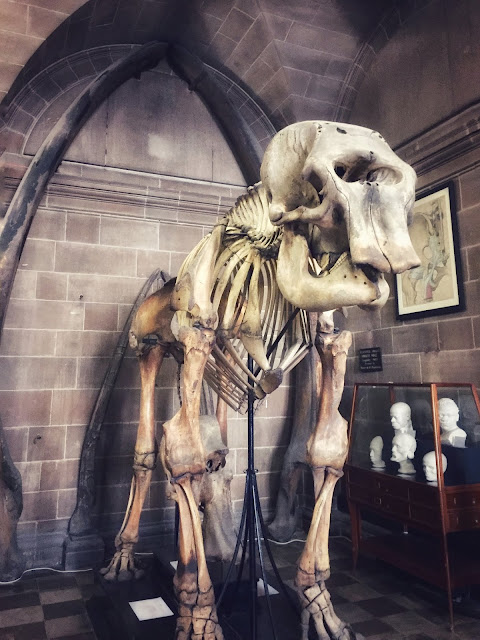

Anatomical Museum

|

| (source) |

You May Also Like

Royal Highland Show | Scotland

29 June 2018

Boseong Green Tea Plantation Light Festival

21 December 2016